What is Thematic Analysis? And How to Apply in Design Thinking

Thematic analysis is a qualitative research method used to identify, analyse, and interpret patterns or themes within a dataset, such as interview transcripts, survey responses, or written texts. It involves systematically organising and examining the data to uncover underlying meanings, ideas, and concepts. Qualitative data presents one of the crucial elements that we seek to collect to understand design challenges as part of the design thinking research phase (e.g. the Explore phase on the Double Diamond Design Thinking). Qualitative data lets us understand people’s needs and build empathy through communicating their feelings and impressions. Methods like interviews, focus groups, and observations suit this purpose ()Design Thinking Tools for Ideation. Tools like the Six Thinking Hats and Empathy Persona Mapping can also produce qualitative data. However, there are several challenges associated with qualitative data analysis due to its descriptive and analytical nature. There is where thematic analysis can be implemented to identify, analyse, and interpret patterns or themes within the data transcripts from any qualitative methods highlighted above.

What is Thematic Analysis?

The thematic analysis is a flexible method for qualitative content analysis that has been widely used during the 20 century to analyse qualitative data collected from interviews, observations, user studies, diary notes, and focus groups through a semantic approach in analysing the collected data. In this method, we review and analyse the data scripts of participants’ answers and try to interpret the answers into codes (codebook), which are keywords that represent the meaning of each part (sentences or paragraphs). Codes with similar meanings are then organised and arranged in themes based on their relevance to each other.

Once we have the generating themes, we revise and organise them to build a narration of the results of the qualitative data collected from all the participants. These results inform the following stages of the design thinking process, identify the opportunities and guide the testing stage to ensure the coherent connection between the outcome of the process and the initial definition of the design problem (How to Use TRIZ in the Problem-Solving Process).

The Approaches of Thematic Analysis

There are two main approaches when conducting the thematic analysis process based on the plan adopted when conducting the thematic analysis of data, either inductive or deductive (Using Inductive Reasoning in User Experience Research):

- Inductive thematic analysis: Based on the inductive reasoning approach, the themes emerged from the data collected without prior identification before the data analysis. This type of thematic analysis can be used as an exploratory tool where we have no previous research about the topic and need to find data that emerge from the qualitative data findings.

- Deductive thematic analysis: In contrast, in the deductive approaches to thematic analysis, there is an idea about the themes before the data analysis, and the codes are assigned to these themes. This type is suitable when we have sufficient data from the literature or previous studies about the topic, and we want to explore how the qualitative data analysis confirms our existing data.

As discussed in my article, Why Design Thinking Doesn’t Work, the design thinking process appreciates uncertainty and identifies innovative opportunities to solve problems with a focus on human needs. Therefore, the inductive approach is more feasible than the deductive one as it maximises the opportunity to identify new information about the situation without prior bias (Five Design Thinking Books to Learn the Principles).

The Role of Thematic Analysis in Design Thinking

When we conduct research design, we focus more on qualitative research methods such as interviews, focus groups and observations because it reflects people’s impressions and can describe their feelings and emotional experience, unlike the quantitative methods (The Role of Storytelling in the Design Process). Therefore, it is essential to have an excellent approach to analysing the collected qualitative data and synthesising the findings in an organised way to explore.

However, analysing qualitative data can be very challenging due to several factors, such as missing part of the data in the narration either by dropping it or getting distracted by other parts. Another challenge is the analysed information can be biased or subjective because it depends on our interpretation of the different situations. Therefore, thematic analysis can help us build a coherent and organised set of data to help us analyse the results.

Pros and Cons of Applying the Thematic Analysis

To effectively use the thematic analysis in design thinking, we need to be clear on the advantages and disadvantages of applying it to mitigate the disadvantages and use it correctly during and after the research phase of the design thinking process. The advantages of using the thematic analysis include the following:

- Flexibility: Thematic analysis provides a flexible approach that can be applied to various research questions and datasets.

- In-depth understanding: Thematic analysis allows a detailed exploration of participants’ perspectives and experiences. It helps uncover rich and nuanced insights into the underlying meanings and interpretations within the data.

- Contextualised findings: Thematic analysis considers the broader context in which the data was generated, considering the social, cultural, and historical factors that shape participants’ views.

- Theory development: Thematic analysis can contribute to theory development by identifying emergent themes and patterns. It enables us to generate new concepts and theoretical frameworks based on the data, contributing to advancing knowledge about the design challenge (How to Apply 5 Whys Root Cause Analysis).

- Researcher reflexivity: Thematic analysis encourages researchers to reflect critically on their biases, assumptions, and preconceptions. It facilitates an iterative data analysis process, allowing for constant refinement and adjustment of themes based on ongoing reflections.

The disadvantages of the thematic analysis are not like points to consider to overcome to achieve practical data analysis, such as the following:

- Subjectivity: Thematic analysis relies on the researcher’s interpretation of the data, which introduces the potential for subjectivity. We can overcome this disadvantage through methods such as inter-rater reliability.

- Time-consuming: Thematic analysis can be a time-intensive process, mainly when dealing with large datasets. The iterative nature of the analysis, involving multiple stages of coding, categorising, and theme development, requires considerable time and effort for better time management (check How to Use the Action Priority Matrix in Time Management?).

- Reductionist approach: Thematic analysis involves condensing and summarising complex data into themes. While this simplification aids in organising and presenting the findings, it can result in a loss of detail and nuance, potentially oversimplifying the complexity of the data, which can also be mitigated using inter-rater reliability.

- Potential bias: Researchers’ biases and preconceived notions can influence the identification and interpretation of themes. Researchers must actively address their preferences, employ rigorous coding techniques, and utilise methods like inter-coder reliability checks to enhance the validity and reliability of the analysis.

How to Conduct the Thematic Analysis?

There are several ways to conduct the thematic analysis. You can use the manual way of highlighting the transcript’s different parts and use sticky notes to organise your codes. If you prefer digital idea organisations, you can use online brainstorming tools. For a complete list of tools, check 13 Online Design Thinking Tools for Mind Mapping, which we used in the example below. Suppose you are dealing with long or multiple interviews where the data becomes too long for the manual thematic analysis. In that case, there are several tools that allow you to manage your codes and themes effectively, such as:

- Dovetail

- EnjoyHQ

- Delve

- Aurelius

- Nvivo

- Dedoose

- MAXQDA

The above software may require buying a license or using a school license in order to use it.

Example of Applying Thematic Analysis in Design Thinking

In this quick example, we will explore how to create the thematic analysis for an interview with a designer about the skills needed in his work and practice. We used part of the interview transcript as an example to show how to develop the thematic analysis.

Step 1: Formalisation

Interviews should be audio or video recorded, and we create a transcript for the answers discussed in the interview. Many of today’s online meeting platforms allow you to generate a much easier transcript than the old manual transcription. Several applications, such as Otter, can help you have real-time transcription. But the problem with these applications is that there may be mistakes and errors in wording during the transcription. So, the first step of formalisation is to clear the transcripts in hand and ensure the accuracy of the transcripts. There are several applications that helps you to do audio recording and real-life transcription such as Otter.

Once we have an accurate and clean transcript, we start by reading the whole transcript to build familiarity with the interviewee’s answers, the words used, the structure of the interview flow, and the answered questions. In semi-structured interviews, for example, we can ask questions that should have been planned earlier to collect further data from the interviewees. We must read the transcript carefully in this interview to get all the extended data.

Step 2: Initial Codes Generation

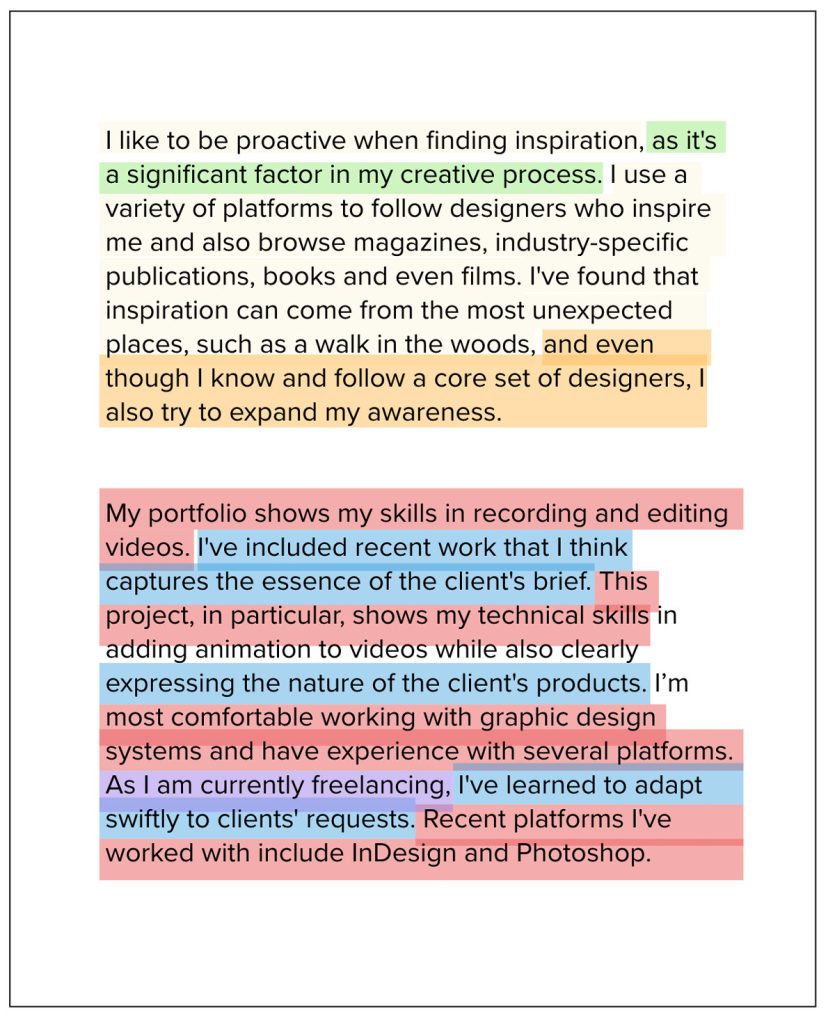

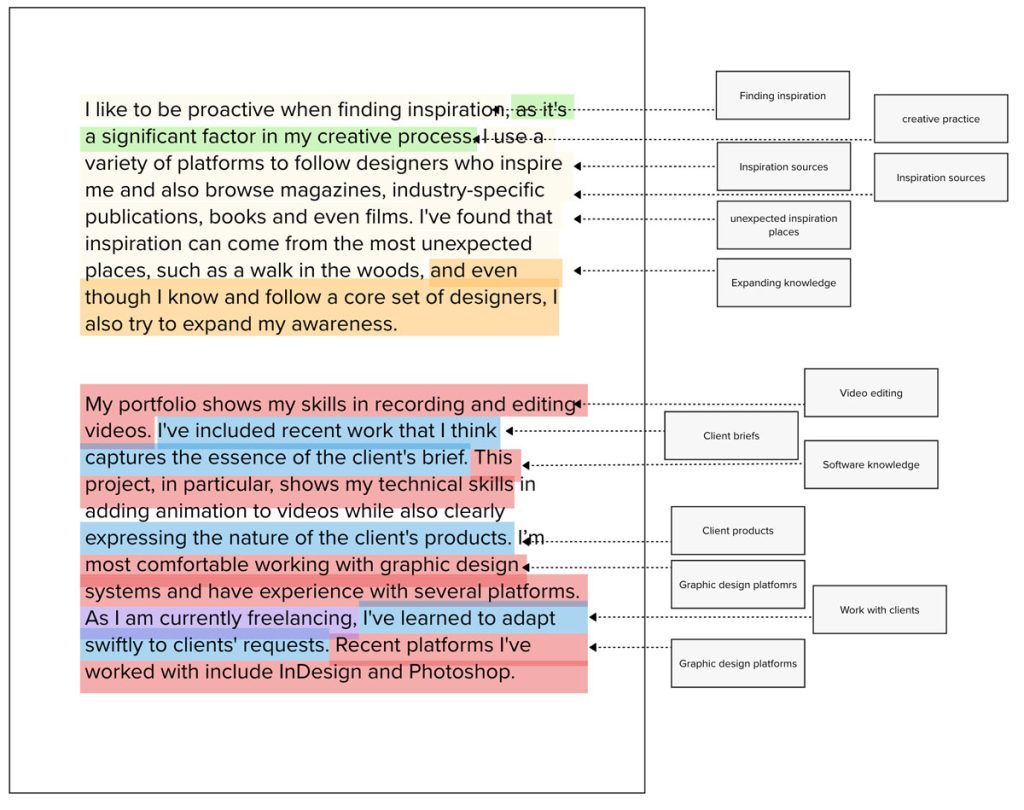

Then we read each line and paragraph thoroughly and tried to interpret or describe what the interviewee wanted to say. We need to read through the sentences several times and see how it links to the paragraphs before and after to understand the context, as in many situations, the interviewee extends or refines their description through the narration.

Then, we assign a code for each sentence, group of sentences or paragraphs to represent the meaning of each part of the narration. Codes are simply keywords to reflect the meanings that the interviewee wanted to say. And each time the interviewee repeats the same point, we assign the same code to map the repetition of the different points through the transcript.

For example, in our example, the interviewee highlighted, “I like to be proactive when finding inspiration.” We assign the code (Finding inspirations) for this interview sentence. Then, if we see another sentence that conveys the same meaning, we assign the same principle. Then, we continue giving codes in each part of the transcript by recording how often these codes are repeated. If we conduct several interviews, we must register how many times each code is replicated across all the interviews.

Step 3: Reviewing the Generated Codes

We often got very involved in the coding process and missed seeing the whole picture.

Once the coding process for the whole transcript is completed, we need to review the codes again to ensure accurate descriptions for each generated code and the assigned sentences.

Step 4: Identifying the Themes

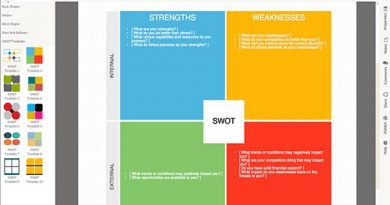

Once we complete the initial coding step, we scan all the created codes from the interview transcript. The codes can be added separately on stick notes (or digital sticky notes ) using manual tools or any qualitative analysis software, as the list above lists.

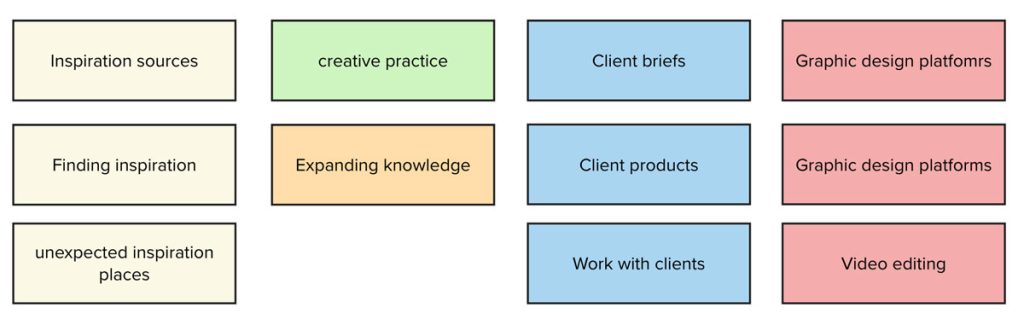

Themes refer to codes that are similar and can be categorised together. We will start to organise the codes based on the similarity of their topic and meaning. You can use several tools to make this organising content easily and quickly, such as Card Sorting and Affinity Diagram. In our example, we find that the following codes can have similarities:

- Inspiration sources

- Finding inspirations

- Unexpected inspiration places

- Creative practice

- Expanding knowledge

The themes evolve from the generated groups as you put the relevant codes in similar groups. Then, you review the generated groups and modify the codes and the groups if needed.

Step 5: Define the Theme Names

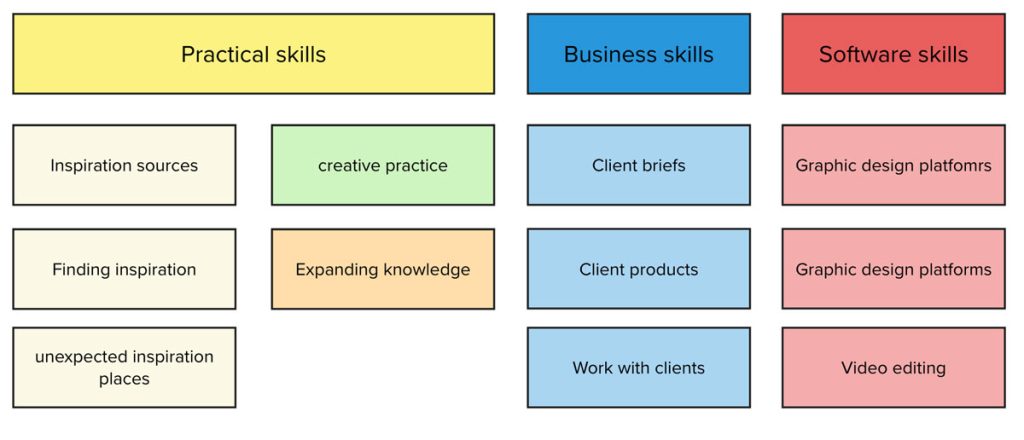

Once the codes are added to groups, this will help us to identify the themes generated. Then, we will need to assign reflective names to these themes. For example, our transcript shows three themes evolved: Practical skills, Business skills, and Software skills. As this example is an inductive theme analysis, the themes generated define a generated idea that can be used to identify the skills needed for a design career.

These findings can then be tested through the solution in the following stages of the design thinking process. If we started with predefined themes (deductive thematic analysis), our findings would confirm the initial hypothesis we needed to test through the qualitative data findings.

Inter-Rater Reliability

As we highlighted earlier, the thematic analysis is subjective and can be biased. You probably noticed that you could suggest other code names and main themes. You may also have other interpretations of the interviewee’s answers. Therefore, we need a method that helps us to confirm that we have developed theme and their accuracy.

One of the methods that we can use is inter-rater reliability. It is a measure of consensus or consistency between two or more independent raters or observers evaluating the same phenomenon or data. It assesses the degree of agreement among raters in their codes and themes.

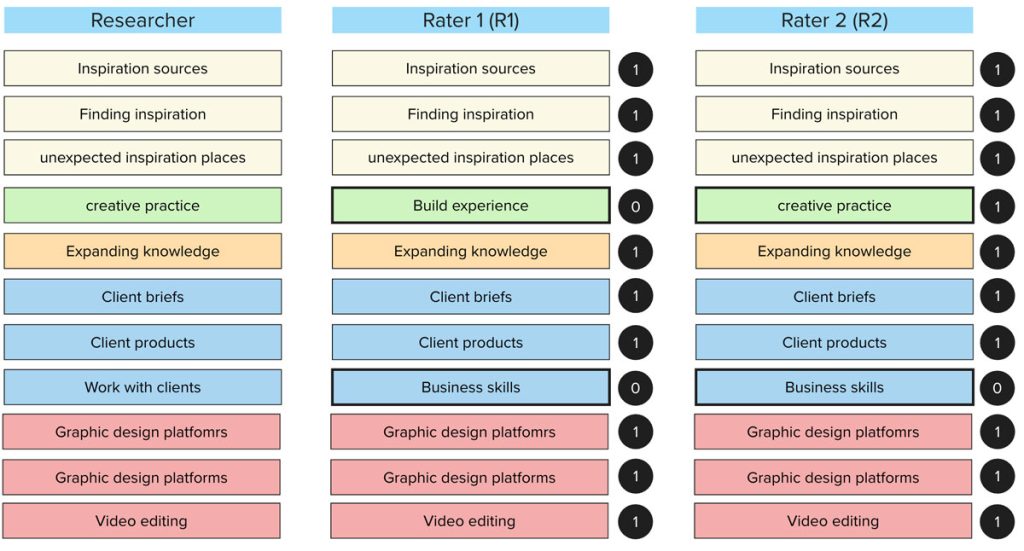

We give the transcript (the entire data set or part) to two raters (coders). The raters can be researchers or fellows with a general idea about the topic, so they have knowledge of the interview conversation and the terms used. However, they shouldn’t be members or involved in the research to avoid any bias or similar thoughts that can turn the procedure useless.

In this example, two raters were asked to review the themes and suggest more relevant theme names if needed. Rater 1 (R1) proposed a change in two code names (Design education and Professional knowledge), while the second rater (R2) proposed a change in one code (Professional knowledge). There is an agreement between the raters on one code while disagreeing with the researcher.

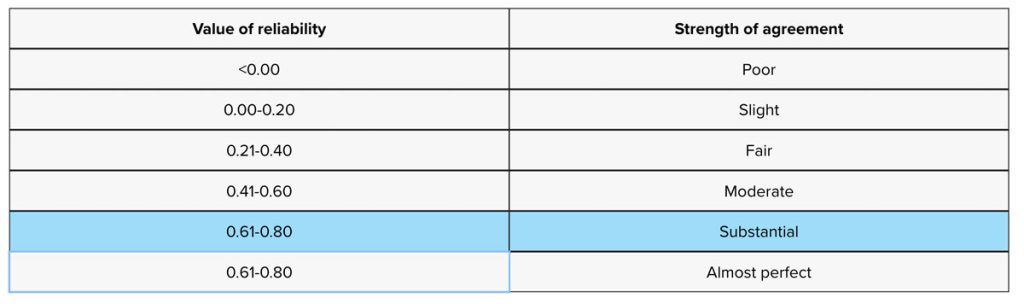

Applying Cohen Kappa for Inter-Rater Reliability

After identifying the level of accuracy of the generated themes using the inter-rater reliability, we need to eliminate the probability of agreeing between the rater due to chance. Cohen’s Kappa is a statistical measure that quantifies the degree of agreement between two raters beyond what would be expected by chance. It considers both the observed agreement and the agreement expected by chance.

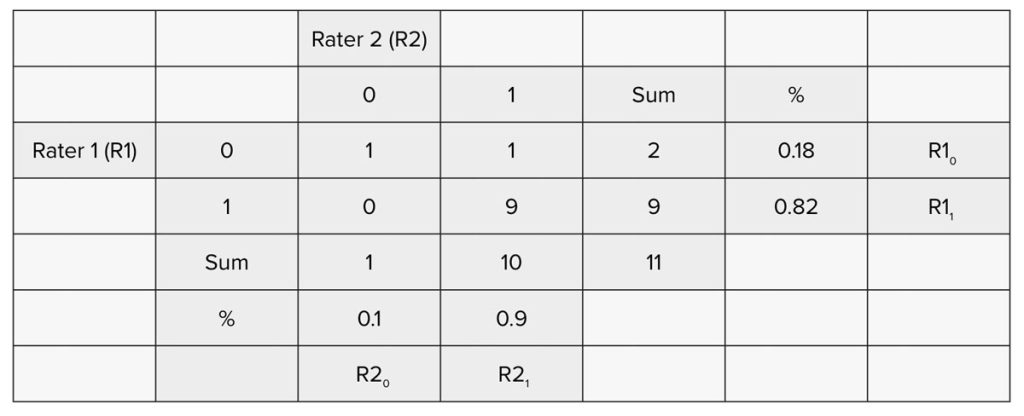

As you can see in the above figure, we use the binary system with the number ‘1’ referring to an agreement with the initial code and ‘0’ meaning disagreement with the initial code. The table below shows an analysis of the agreement of both the first and second-raters of the agreement data.

Based on the above table, we can calculate the Cohen Kappa for the inter-rater reliability as follows:

First, we calculate the Pa value, representing the raters’ observed agreement. Remember, the percentage of the agreement here can include the agreement by chance as well.

Pa = (N00+ N11) / 11

= (1+9) / 11 = 0.9

- Pa: Relative observed agreement amongst raters

- N: Total number of codes

- N00: The raters agreed with each other but disagreed with the initial researcher codes.

- N11: Both raters agreed with the initial researcher codes.

Now, we will calculate the probability of agreement between the raters based on the chance through the following equation:

Pe = (R10 /N) * (R20 /N) + (R11 /N) * (R21 /N)

= 0.18 * 0.1 + 0.8 * 0.9 = 0.74

- Pe: Hypothetical probability of chance agreement

- R10: Total disagreed codes by the first rater

- R11: Total agreed on codes by the first rater

- R20: Total disagreed themes by the second rater

- R21: Total agreed themes by the second rater

Now, after calculating the agreement probability and the agreement based on the chance, we can calculate the Cohen Kappa factor as below:

K = (Pa-Pe) / (1-Pe)

= (0.9 – 0.7) / (1-0.7) = 0.67

Based on the Cohen Kappa scale shown in the figure above, we can find that the agreement level is Substantial, meaning there is a very good agreement between the raters and the initial researcher. As a result, we have a confirmation of the accuracy of the generated codes from the transcript. As a sequence, we can confidently depend on the findings in defining the problem that we aim to solve during the design thinking process.

Conclusion

As qualitative data plays a particular importance in the design thinking process, we need a methodology that allows us to analyse the qualitative data, such as the thematic analysis, which provides a way to interpret the qualitative data into codes. Then, we explore the similarities between those codes to see the evolved themes from the codes. However, thematic analysis can be subjective and biased. Therefore, we can confirm the results and ensure their accuracy through the inter-rater reliability process, where we ask two raters to read the transcript and produce codes for it to compare the rater’s results and the initial researcher who developed the codes in the first place. Then, we explore how to quantitatively confirm that the agreement between the raters is not a subject of chance through tests such as the Cohen Kappa test to evaluate the level of agreement between raters. This methodology helps us to develop an evidence-based design process that we can apply in a wide range of applications that requires high accuracy in understanding and defining the problem.

Summary:

Thematic analysis is a qualitative research approach employed to identify, analyze, and interpret patterns or themes within a dataset, which can include interview transcripts, survey responses, or written texts. It entails a systematic process of organizing and examining the data to reveal underlying meanings, ideas, and concepts. In the realm of design thinking research, qualitative data serves as a vital component for comprehending design challenges during the research phase.

Inductive thematic analysis: Inductive thematic analysis follows an approach based on inductive reasoning, where themes emerge from the data during the analysis process without predetermined identification. This method is particularly useful as an exploratory tool when there is limited prior research on the topic, allowing for themes to naturally emerge from the qualitative data findings.

Deductive thematic analysis: In contrast, deductive thematic analysis involves pre-existing ideas or themes that are identified before the data analysis begins. Codes are then assigned to these predetermined themes. This type of analysis is suitable when there is sufficient data available from the literature or previous studies, and the aim is to explore how the qualitative data analysis aligns with or confirms the existing knowledge on the topic.

1. Familiarisation: Immerse yourself in the qualitative data to understand its content, context, and nuances.

2. Initial coding: Assign codes to relevant segments of the data without focusing on themes.

3. Collating codes: Group related codes to form potential themes, looking for patterns and connections.

4. Reviewing and refining themes: Examine potential themes, refining and revising them to accurately represent the data.

5. Defining and naming themes: Develop clear definitions and descriptive names for each theme.

6. Generating a thematic map: Create a visual representation to illustrate the relationships between themes.

7. Analyzing and interpreting themes: Conduct a deeper analysis of each theme, identifying key findings and patterns.

Writing the report: Summarize key themes, their definitions, and supporting evidence, providing examples and ensuring clarity for the audience.